Hellraiser Actor, Simon Bamford — A Portrait Session on Real Film

Across theatre, film, and television, Simon Bamford has built a career grounded in precision and physical awareness. Audiences know him first through the enduring imagery of Hellraiser and Nightbreed — roles that made him a figure within the language of British cult cinema — yet his roots are theatrical. Trained for the stage, his work is defined by an understanding of stillness: the ability to hold attention through exact posture and measured timing. That quality is rare; it cannot be taught quickly, and it photographs differently from performance designed for the screen.

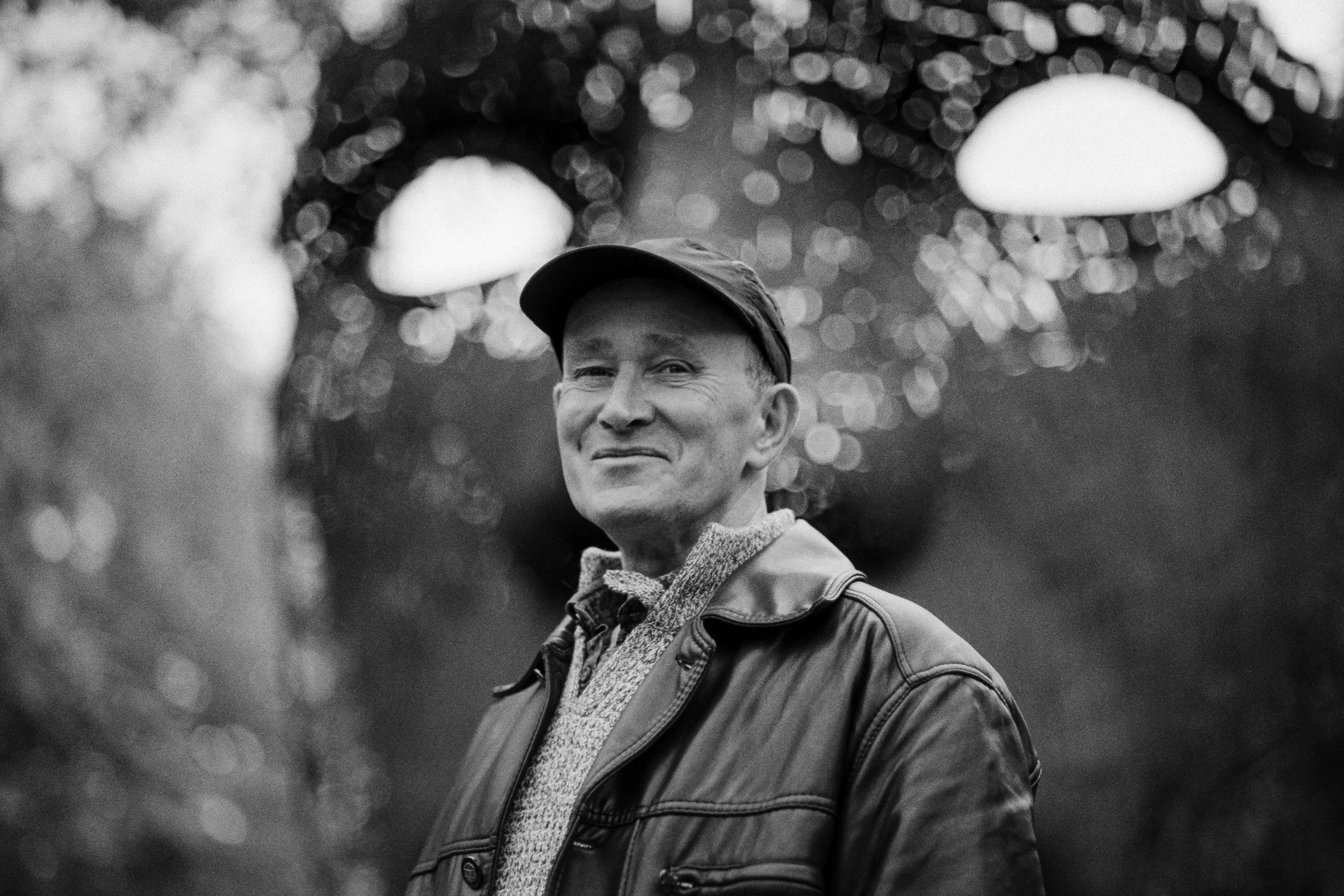

Simon Bamford beneath the large sculpted face — a quiet moment where scale and expression meet. Shot on Rollei RPX 400 with the Takumar 85 mm f/1.8 on the Canon F-1.

Simon’s career has spanned more than thirty years of transformation in acting and production technique, but his method has remained constant. He builds character through observation. Each gesture is reduced to its simplest form until nothing can be removed without weakening meaning. That approach resonated completely with my own practice in film photography, where reduction and control replace excess and convenience.

He is currently preparing for his next project, Black Eyed Children 2, which begins filming soon in Hungary. The film continues his connection to psychological horror but carries an introspective tone. We decided to build a portrait session that captured that transition — the space between the actor and the role, when the persona begins to shift but has not yet settled.

Simon is a huge fan of black and white, chiaroscuro lighting, and the craft of image-making that reveals form through contrast. He approaches photography and film with the same respect he brings to performance — understanding that shadow defines structure, and restraint creates power. His appreciation for the interplay between light and darkness made this session more than a portrait sitting; it became a shared study in tone, texture, and control — the same language that drives both cinema and fine black-and-white film.

On Location

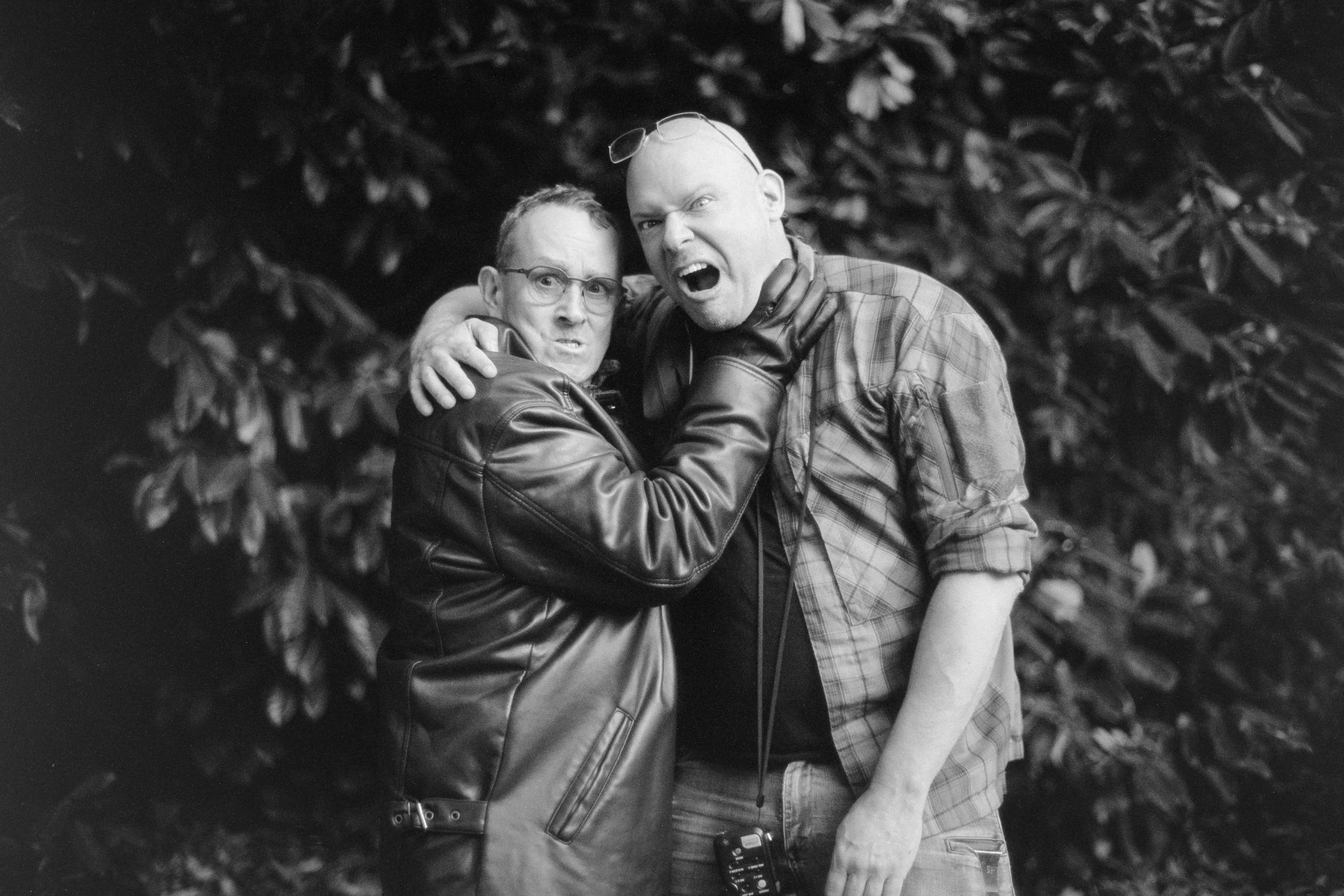

A brief lighter moment during the session. These frames often appear unplanned, but they come from attention, timing and knowing when not to interrupt the subject.

I work nationally, usually within the West Midlands, Warwickshire and the areas around Leamington Spa. For Simon, it was a national shoot that I was very happy to travel for. We worked outdoors in late afternoon, under the restrained colour of declining light. The location offered texture — timber, stone, rough surfaces — but strict rules: no lighting, no stands, no tripods. Every adjustment had to come from position and timing.

Normally, my work depends on structured lighting. I travel with parabolic modifiers, diffusion panels, and Fresnel units; every portrait is sculpted, not found. I do not rely on “natural light,” because unshaped light rarely respects the subject. But on this occasion, control had to come from geometry alone.

The discipline reminded me of the earliest documentary and cinematic photographers who built exposure from what was available, balancing highlight and shadow through observation. For this session, the environment itself became the lighting rig. A white wall served as reflector; the ground plane lifted shadow fill; glass in the background redirected a faint, usable shimmer onto Simon’s face. Every decision became about alignment — how to place an actor within the mechanics of light rather than impose light upon him.

“Martin is truly one of the best photographers I have encountered in the last 64 years. A consummate professional who really understands not only his craft, but the technical wizardry that enables it. He is so easy to work with.”

Presence and Collaboration

Simon approached the session as work, not exhibition. He arrived prepared, aware of what we were trying to capture, and immediately understood that this was an exploration of tone. Between frames he moved in increments — a half-turn of the head, a change in direction of gaze, the smallest shift in posture.

He reads light instinctively. Years of stage work teach actors to monitor illumination peripherally — to sense when they have stepped out of their own key light without breaking focus. That skill translated perfectly here. Without any lighting equipment, he adjusted himself to catch reflection from the wall, allowing me to keep composition fluid.

The resulting rhythm felt cinematic in the purest sense: a scene rehearsed, refined, and then played once. Each exposure became a take. The camera acted not as an observer but as audience, recording a performance distilled to stillness.

My Leica M3— the rangefinder I used for much of the session. Its focusing system lets me watch the subject continuously both inside and outside of the frame, keeping expression and timing uninterrupted.

The Cameras — Design as Language

Each camera was chosen because of the way it interprets light and movement. Their mechanical differences shaped both pace and intention.

Leica M3 + Voigtländer 50 mm f/1.1 Nokton

The Leica handled immediacy. Rangefinder focusing allows uninterrupted observation — I can see the subject even as the shutter fires. The Nokton, wide open, produces depth rather than blur; its rendering is cinematic, with a slow fall-off that gathers attention around the eyes. It excels at drawing out subtle expression, which was the core of this session.

Canon F-1 + Pancolar 50 mm f/1.8 (zebra) / Asahi 85 mm f/1.8

The F-1 brought discipline. Its mirror and shutter mechanics demand intention; each exposure is deliberate. The Pancolar, an East-German optical design, offers crisp micro-contrast and plane separation that reinforces structural composition. The Asahi 85 mm adds gentler rendering — a natural fall-off that respects skin tone. Together they allowed me to alternate between definition and atmosphere depending on Simon’s energy.

Contax IIa + Zeiss Sonnar 50 mm f/1.5

The oldest system of the three, it introduces texture that belongs to another era. The Sonnar design yields luminous highlights and dense mid-tones; its imperfections are part of its vocabulary. It was used for the most introspective sequences — the frames where Simon’s expression compresses inward, caught halfway between actor and role.

Working across these three mechanical philosophies was intentional: 1930s engineering through 1970s refinement. Each represented a different rhythm of seeing. The Leica encourages anticipation; the Canon demands construction; the Contax enforces patience. Together they mirrored Simon’s own range from instinct to precision.

Simon holding tension in the frame, photographed on the Canon F-1 with the Takumar 85 mm f/1.8. This focal length lets me work close enough to stay with expression, while giving the character room to sit inside the image.

Film, Chemistry, and Intention

All images were made on Rollei RPX 100 and Rollei RPX 400, developed in 510 Pyro. This combination was selected for latitude and permanence. Pyro developers are exacting: they stain the negative, compressing highlights, expanding shadow tone, and embedding a visible record of density into the emulsion. Every print that follows carries that signature.

RPX 100 served for stable light — its fine grain and smooth curve reward careful exposure. RPX 400 took over as the sun fell, its structure holding coherence under low-contrast reflection. The Pyro developer unified both, producing negatives with a restrained warmth and long tonal reach.

There is no digital safety net in this process. Exposure error is permanent. Yet that finality brings clarity. Each frame demands thought before it is made, much as an actor fixes a gesture before stepping into a scene. The medium itself becomes an instrument of discipline.

When the rolls dried, the density of tone confirmed that the decision to work without equipment was correct. Shadows printed cleanly; mid-tones breathed; highlights held edge detail. The negatives feel carved rather than captured.

Geometry of Light

One frame defines the method. Simon stands beside a timber structure, his hand resting forward. The light bounces off a pale wall, grazing his face with enough strength to separate features without flattening texture. The blurred rail in the foreground pulls the eye to the hand, then upward through the composition to his gaze. That sequence of movement within the frame mirrors the rhythm of performance itself: gesture → presence → connection.

Light from a nearby wall lifts Simon Bamford’s face just enough to reveal thought without expression. Shot on Rollei RPX 400 with the Voigtländer 50 mm f/1.1 on the Leica M3, it shows how quiet light and measured focus can hold more presence in a performance.

Such control came only through reflection, with no location lights to shape the scene. The bounce lasted seconds before the sun dropped; there was no second take. The exposure landed precisely on the border between shadow and highlight, giving the negative that subtle tension between density and air — the point where still photography and cinema share common grammar.

Simon in the space between himself and the role. This frame was made on the Leica M3 with the Voigtländer 50 mm f/1.1 Nokton — a fast lens that lets me work close and keep expression intact, drawing out character without interrupting the moment.

The Cinematic Dialogue

For viewers who come from the world of film and cinema, these portraits connect directly with Simon’s screen work. They hold the same psychological gravity that defines his performances in Hellraiser and Nightbreed, yet without movement or sound. What remains is presence — a distilled fragment of the same character language, translated through silver and chemistry.

The camera becomes a silent collaborator, not a spectator. The resulting images are not promotional stills but continuations of performance. They preserve what happens between words, where emotion has no cue.

The Photographer’s Perspective

From a photographic standpoint, this session is a demonstration of control without apparatus. When lighting and tripods are removed, the remaining tools are observation, timing, and mechanical fluency. Each camera was used at its optimal point: the Leica for intuitive rangefinder focus, the Canon for deliberate construction, the Contax for depth and atmosphere.

Shooting film under such limitations exposes competence immediately. There is no histogram, no preview, no rescue. The RPX films developed in 510 Pyro respond honestly — if the exposure is wrong, the negative declares it. That exposure discipline is the foundation of professional film work.

The absence of manufactured light forced an exact reading of surface reflection. White walls became diffusers; ground planes became soft fill; Simon’s own pale clothing served as moving reflector. Every decision existed within physics rather than electronics.

Simon suspected I’d missed a frame and the consequences were immediate. I am still alive to write this article, however — evidence that film photographers are harder to kill than they look!

The Analogue Continuum

For the analogue reader, every negative from this session is an artefact — a physical record of collaboration. It can be revisited in a century and reinterpreted in the darkroom, independent of transient technology. This is the quiet permanence that defines film: an unbroken chain from exposure to object.

The slow rhythm of film photography mirrors the discipline of theatre. Both demand rehearsal, repetition, and measured execution. Loading, metering, focusing, exposing, and developing are not rituals of nostalgia but deliberate acts of attention. They create the conditions for authenticity.

When two crafts built on precision meet — acting and analogue photography — the result acquires a different weight. It is not about image or likeness; it is about presence made tangible.

Simon Bamford photographed with the Asahi Takumar 85 mm f/1.8 on 35 mm film. The lens has a calm, unforced way of rendering midtones, which suited the quieter moments in the session.

Reflection and Continuity

As the final negatives hung to dry, the tonal curve revealed everything we had hoped for: clean highlights, articulate mid-tones, and grounded shadows. Each frame carries a quiet rhythm — light folding across performance, performance responding to light.

The session stands as a study in constraint and adaptation. For me, accustomed to constructing light, it reaffirmed that control can exist without equipment if understanding and craft are applied. For Simon, it became another performance measured not in dialogue but in seconds of exposure.

Together we built a sequence that bridges cinema and photography — both founded on timing, awareness, and trust in craft. The outcome is neither portrait nor still; it sits somewhere in the space between, where the mechanics of cameras and the discipline of acting share the same vocabulary.

Closing Observation

Film, at its highest level, is not a matter of nostalgia but of integrity. It enforces patience, demands accuracy, and rewards understanding. The collaboration with Simon Bamford embodies that principle. His presence brings the cinematic world into the static frame; the film material translates it into permanence.

Having an on-set assistant changes everything. While I work through the cameras, they keep the session moving — fresh film loaded, light checked, positions managed, and the next setup ready before I need it. It keeps the rhythm intact so the performances don’t break. Contax IIa and a 1939 Sonnar 50mm f/1.5 lens. Anna keeps my work moving and can be followed on her instagram here.

In an era defined by speed, this session exists as resistance — proof that true craft still relies on human judgment, mechanical precision, and the chemistry of silver halide meeting light.

By Martin Brown | Liquid Light Whisperer

All images in this article were developed and scanned in-house and UK-wide lab at Liquid Light Lab, our dedicated 35 mm film development and studio based in Leamington Spa. Send in your film and you’ll get exceptional results, up to 60MP TIFF and JPEG scans, and rare pyrogallol for exceptional black and white images.