Leica M5 — The Last True Leica

Front view of the Leica M5 in black chrome. The viewfinder window, metering cell, and shutter release sit in perfect alignment along the heavier brass front plate. It’s a design that feels engineered for work rather than display — robust, balanced, and unmistakably Wetzlar.

Built in Wetzlar from 1971 to 1975, the Leica M5 was the last M-series camera finished under Leica’s traditional adjust-and-fit system — bench assembly by individual technicians who tuned each unit by feel, not by stopwatch. After this, Leica adopted team-line methods in Midland and later Solms. The M5 marks the end of that hand-adjusted era: the last rangefinder that feels made rather than produced.

This review comes from the perspective of a working photographer — someone who uses the M5 as a daily tool, not a display piece. Both of mine, one in black chrome and one in silver, are in constant rotation for commissioned work and personal projects alike. The camera’s meter and ergonomics make it one of my favourite ways to shoot when I don’t want to carry a handheld meter. It’s fast, balanced, and deeply reliable, translating directly from professional use to how I document my own life and memories. Whenever I run the negatives through the Liquid Light Lab, I am never disappointed.

I own one in black chrome and one in silver chrome. The camera colours help me when I work; black and white film is in the silver chrome camera, and colour film is always in the black version. Both are daily-service tools that earn their keep. They are quiet, precise, and quicker in practice than reputation suggests. The M5 is the metered M I trust when light or deadlines give no margin for error.

Historical context — Leitz, Wetzlar, and the shift to Midland

By the late 1960s, Ernst Leitz GmbH was a company in transition. The family-run structure that had sustained Wetzlar since the 1920s was under pressure from rising West German labour costs and a global camera industry shifting toward automated production. In 1965 Leitz Canada had been established in Midland, Ontario, under the technical leadership of Walter Mandler. Initially the Canadian branch produced lenses and optical elements, but management soon saw it as a potential site for cost-controlled assembly.

At the Grand Canyon’s North Rim with one of my Leica M5s — photographed by Craig Sheffer. The M5 is my working companion on the road, equally at home on assignment or documenting moments like this with friends.

The M5 therefore arrived at a structural turning point. Wetzlar craftsmen could still hand-fit gears and drums to individual tolerances, but each step cost more than an equivalent line process in Japan. When the M5 sold slowly, Leitz treated the project as proof that mechanical excellence alone could no longer carry the market. The decision to move final assembly of the successor M4-2 to Midland was not a punishment but an act of survival.

Within Leitz, the change split opinion. Traditionalists feared that team-line assembly would dilute the culture of precision; younger managers argued it was the only way to keep Leica solvent. In practice, both were correct. The M5 stands at the hinge between the artisanal Wetzlar years and the industrial era that followed. Its production run of just under 34 000 bodies coincided with the last phase of single-technician bench assembly — an operating model that ended when the Midland line began in 1977.

That historical moment gives the M5 its distinct aura. It isn’t nostalgia; it’s the texture of an industrial method at full maturity just before extinction. Every smooth shutter pull and perfect frame spacing feels like the product of a company still run by engineers rather than managers.

Why the M5 had to happen

By 1970, the professional market was changing shape. Photographers were standardising on SLR systems with full-aperture TTL metering — Nikon F, Canon F-1, Pentax Spotmatic F, Olympus OM-1. Every press and studio job expected through-the-lens measurement and a ground-glass preview. Leitz either integrated metering or risked irrelevance overnight. The M5 was their engineering answer: TTL metering without mirrors, battery dependence limited to the meter only, and total backward compatibility with M lenses.

That ambition came with cost. Integrating a meter meant re-engineering the shutter crate, the film plane, and the chassis depth. The result was a body a few millimetres taller and thicker, but structurally stronger than any earlier M. When people complained about size, they were really complaining about priorities: Leica built precision when the market wanted price.

Roy’s Motel Café on Route 66 — metered with the Leica M5’s central spot to hold the white building tones just below mid-point, preserving sky density and shadow contrast without losing highlight or shadow texture in desert light.

Design authorship — who actually built it

The M5’s architecture belongs to Willi Stein, mechanical lead since the Leica M3. Industrial styling came from Ludwig Leitz Jr. with Paul-Hubert Deschamps, who shaped the front slope and finder window geometry. Walter Mandler was at the optical bench designing Summicrons, not camera bodies. Confusing the two is common; separating them restores credit to the engineers who preserved mechanical purity while modernising function.

The real numbers — production that shows intent

Official Leica ledgers list 33,881 units made between 1971 and 1975: roughly 22,685 black chrome, 10,396 silver chrome, and about 1,750 Jubilee editions within the total. The spread reflects the market’s slow acceptance — silver dominated the early run, black the later. Compare that to the 220,000 Leica M3s built in the fifties and you see how few M5s exist. Scarcity came not from rarity marketing but from halted momentum: Leitz built until dealers stopped ordering.

Inside those years are quiet revisions: the early two-lug body, the later three-lug, a minor meter-arm pivot change, and a thicker galvanometer window from mid-1973. None alter the shooting character; all speak of small mechanical housekeeping by a company still run by engineers, not accountants.

Materials and tolerances

Top plate and base are milled brass; the chassis core is machined alloy with brass bearing seats. Screws are stainless, not plated. The deeper shell resists flex; the thicker plate damps resonance. Every control rides on hardened steel pivots lubricated sparingly — three drops total in the entire advance train. That restraint is why an unserviced M5 can still feel like a camera built last week.

Chassis, shutter, and transport

Internally the M5 follows the M4’s shutter principle: horizontally-running rubberised cloth curtains on precision-balanced drums, brake timed to 1/1000 s. But the chassis is heavier — a one-piece milled shell rather than the multi-part stamping of earlier Ms. The thicker top plate adds torsional rigidity; the brass body absorbs vibration, letting the shutter whisper instead of click. Film transport uses a new sprocket drum with roller bearings and tighter pitch control. Frame spacing is remarkably even — a trivial detail until you scan thousands of frames and see consistency reel after reel.

Metering — Leica’s most elegant hybrid system

Leica’s brief was uncompromising: a TTL meter with true spot precision, entirely mechanical shutter, and full visibility inside the finder. Their solution — an ≈7.5 mm CdS cell mounted on a swinging arm entering the optical axis when cocked — remains one of the cleanest mechanical-electrical integrations in camera history. When you wind the advance, the arm moves into position; when you release, it retracts instantly to protect the film plane. The galvanometer needle, driven by voltage from that cell, couples through a rheostat to the shutter-speed dial. Exposure correction appears as motion: you watch the needle drift and align it to the index. No clicks, no lights, no guesswork.

Every part of that chain is analog: light → resistance → current → torque → needle. The feedback loop is continuous and silent. Once the muscle memory forms, metering becomes reflexive — you sense exposure through motion.

Model portrait on Leica M5 with Voigtländer 50 mm f/1.1. During a live shoot, the M5’s match-needle meter let me adjust exposure on the fly without leaving the finder — proof of how usable the system remains when working fast and wide open. The finder allows me to manually focus extreme apertures of f/1.1 exceptionally quickly.

The meter’s coverage is roughly the inner 12 % of the frame, far tighter than the M6’s averaging field. That single design choice makes the M5 a precision instrument for slide or cine stock; it reads what matters, not everything around it.

Engineering and calibration detail — the M5 as a mechanical-electrical hybrid

Inside the M5, the metering assembly is a miniature instrument laboratory. The galvanometer’s needle arm pivots on sapphire bearings; its coil is wound with ultra-fine copper wire rated at 1 000 Ω, chosen to balance sensitivity with vibration damping. The CdS cell on the swinging probe is mounted in a blackened brass collar to prevent internal reflections. The return spring that retracts the probe uses a constant-tension strip sourced from the same supplier that built timing parts for Leitz microscopes.

When the shutter is cocked, a cam on the advance drum lifts the probe into position. Its arc is synchronised with the rangefinder cam via a small lever so that the meter reads precisely through the taking lens’s central field. The galvanometer output is filtered through a damping resistor network to prevent needle oscillation. All of this happens without a single transistor.

Calibration at the factory involved a bench light source at 2850K and a reference photometer. Technicians adjusted a pair of rheostats: one for full-scale voltage, one for linearity across the stop range. Once set, drift was minimal. The camera’s meter relies on current flow measured in microamps; at that scale, contact cleanliness matters more than voltage stability, which is why the MR-9 adapter’s fixed-output design is ideal.

Understanding this internal logic changes how you use the M5. When you see the needle move, you’re watching an electromechanical equation solved in real time — not a microprocessor sampling but a direct analogue of light energy bending a coil inside a magnetic field. It’s the closest any camera comes to letting you see exposure itself.

Neon-lit portrait on Leica M5 with Voigtländer 40 mm f/1.2. Using the M5’s overhanging shutter dial, I was able to meter rapidly across the frame and hold detail in both the highlights and the face — proof of how responsive the spot-meter system remains in complex lighting.

Power and calibration

The PX625 1.35 V mercury cell is long gone. Modern operation relies on either an MR-9 adapter with a 1.55 V silver-oxide cell (best long-term) or the Wein MRB625 zinc-air substitute. Once the camera is calibrated for the chosen voltage, readings remain linear. My black body was serviced fifteen years ago and still meters within 1/6 stop of a Sekonic L-508. The circuit draws microamps; battery life is measured in years, not rolls.

Battery reality in long-term use

The MR-9 adapter effectively restores the 1.35 V operating voltage curve. I replace cells as needed, check against a handheld meter at random intervals, and never adjust mid-roll. The system’s linear response means exposure variance roll to roll stays within lab tolerances. You can trust the needle more than many modern TTLs that depend on firmware assumptions.

The shutter dial that defines usability

The overhanging shutter dial is the M5’s signature. Coaxial with the release and geared to the internal speed cam, it allows fingertip control without leaving the finder. On reportage work it’s transformative: exposure becomes part of framing, not an interruption to it. Every other M after the M4 returned to a smaller top-plate dial; only the M6 TTL partly restored the concept. But the M5’s dial feels hydraulic — the perfect resistance, audible only to the user’s skin.

In bright-dark transitions — stage work, late afternoon exteriors, mixed tungsten — I ride that dial constantly. The camera becomes a physical light meter: you feel exposure change through resistance and needle travel. It’s a rhythm, not a process.

Finder and focusing authority

Magnification is 0.72× with the finder displaying framelines for 35, 50, and 90mm lenses on early bodies. Later three-lug versions introduced 135mm framelines and a slightly brighter illumination window. The optical formula remained unchanged; the upgrade simply reflected Leica’s plan to standardise frame sets with the upcoming M4-2 and M6 designs..

Shutter speeds appear along the bottom edge, the first M finder to show them. The 68.5 mm base length (effective 49.3 mm) provides excellent accuracy with lenses as fast as f/1.1. Rangefinder coupling tolerance is ± 10 µm — about one-tenth the thickness of a human hair — which is why, when aligned, focus feels like a snap rather than a guess.

The prism assembly itself sits deeper within the top plate than on previous Ms, giving slightly improved flare resistance. Leica’s beam-splitter coating of the period, a magnesium-fluoride layer on crown glass, has proven stable; finders often remain clear without re-silvering even after fifty years.

Road trip through Ireland — photographed on Leica M5 with Voigtländer 40 mm f/1.2, Babylon 13 black and white film. The image captures the camera’s precise metering in complex tonal depth in fast-moving light across the open road.

Viewfinder optics and mechanical lineage

The M5’s finder was a clean-sheet redesign even though it retained the familiar brightline geometry. The prism group uses two bonded optical blocks rather than three, reducing internal reflections and easing alignment. The illumination window on the front plate feeds light through a small diffusing tunnel to the frameline mask, ensuring even brightness without flare. The eyepiece lens is slightly recessed compared to the M4, an improvement that prevents side reflections when working under studio lights.

The in-finder shutter-speed display uses a mirrored drum linked to the speed cam. As the dial turns, engraved numbers rotate across the lower edge of the viewfinder field, lit by the same illumination channel that powers the framelines. The result is legibility without clutter — a single line of digits floating beneath the scene.

Parallax correction remains mechanical. A steel cam moves the frameline mask forward as focus shifts closer, compensating both vertical and horizontal offset. The precision of this movement is one reason the M5 retains perfect alignment decades later; the guide rails are hardened and ride on tiny phosphor-bronze bushings.

Where the Leica M3’s finder feels jewel-like, the M5’s feels surgical. It’s brighter, flatter in contrast, and less romantic but more functional. For long shooting days, that difference reduces fatigue — the optical equivalent of a clear monitor compared to a nostalgic glow.

Optical path, framelines, parallax

Leica’s finder projects framelines via a condenser and prism; the parallax correction mask moves with focus distance through a cam linked to the rangefinder roller. The M5 adds the shutter-speed display along the lower edge — a simple addition that eliminates guessing during fast changes. You always know where you are in time as well as light.

Dimensions, balance, and field ergonomics

Official size: 150 × 84 × 36 mm. Weight: ≈ 740 g (silver), ≈ 775 g (black) with battery. Those numbers suggest bulk, yet the handling contradicts them. The deeper body shifts mass closer to the lens axis; the camera seats naturally into the hand. Strap lugs are lower, so the body hangs flat against the torso instead of tilting outward — a subtle but significant improvement during long assignments.

Many critics of the day called it “too big.” In use, that complaint vanishes by the second roll. The M5’s volume isn’t excess; it’s stability. When shooting wide open with 50 mm lenses at 1/30 s, the extra mass keeps alignment perfect.

Lens compatibility — what clears, what doesn’t

Any lens 28 mm or longer with standard rear geometry mounts safely. Do not collapse collapsible Elmars or Summars; the meter arm occupies the space they retract into. Avoid early 28 mm Elmarit v1 and certain early Canon LTM 28s with deep rear collars unless tested for clearance. Everything else — 35 Summicron, 40 C Summicron, 50 Sonnar, 90 Tele-Elmarit — couples perfectly. The meter arm’s arc clears most bayonets by design; its pivot cam was machined for a ± 0.05 mm tolerance.

How I meter in practice

Contrast portrait: meter the face, bias 1/3 stop under to preserve negative density; the film’s latitude protects shadows.

Backlight: ignore the rim light, swing the spot to the subject’s cheek, shoot.

Fast-changing light: keep finger on the dial, needle in sight. The analog motion shows direction and degree faster than LEDs ever can.

Night exteriors: meter a neutral mid-tone, open one stop for skin, test on first frame.

This analogue method links mind and mechanism. Nothing blinks, nothing distracts. It’s control by intuition, not by algorithm.

In the field — a working camera, not an artefact

Both my M5s have seen full-day work: portraits, editorial travel, and cinema-adjacent stills. During the A River Runs Through It 30-year anniversary road trip with Craig Sheffer, I carried them through desert heat and city dusk. The meter never drifted, the shutter never hesitated. In bright Mojave sun I could spot-meter his face under a brim and ride exposure as clouds passed. It’s the kind of fluidity that makes the tool disappear.

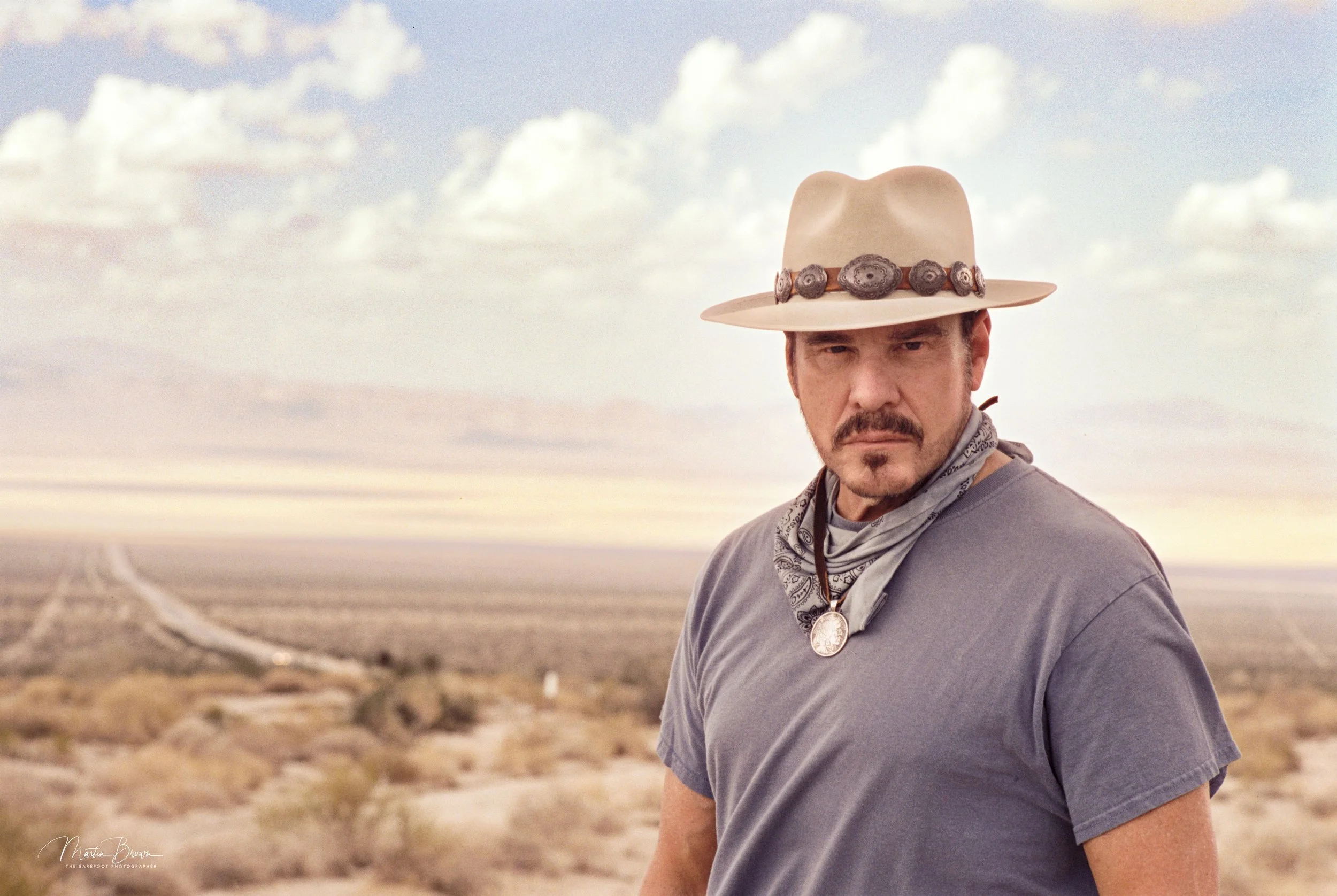

Craig Sheffer in the Mojave Desert — photographed on Leica M5 with Voigtländer 40 mm f/1.2. The selective spot meter and overhanging shutter dial made fine exposure control immediate under shifting desert light.

Professional use and accessory integration

The M5 accepts most M-series accessories: the Visoflex III reflex housing fits perfectly, providing ground-glass focusing for macro or telephoto work. The Leicavit rapid winder attaches via a custom baseplate coupler, giving a two-stroke advance without compromising the meter linkage. With the Leitz 90 mm f/2 Summicron, the combination handles portrait sessions elegantly; the deeper body provides better grip and counter-balance.

Filter users benefit from the precise spot meter. When shooting colour negative or cine stocks such as Vision3 250D, a warming or diffusion filter can be metered through directly without compensation charts. In studio settings, the selective meter makes flash ratio balancing easy: measure the key light spill on the subject’s cheek, adjust fill to taste, and the exposure lands exactly where you intend.

On location, the camera’s mechanical damping pays off. Long exposures at 1/8 s on a tripod show no frame overlap. The shutter release, a polished steel stem with minimal travel, breaks at roughly 100 g pressure — half that of an F2 — producing almost no vibration. These details explain why photographers who actually work with film keep returning to the M5: it isn’t just about charm, it’s about consistency.

Operating discipline — making it disappear

Advance two frames, confirm counter. Cock the shutter and check needle wake-up. Visualise the meter spot; keep the index finger on the overhanging dial. Adjust by feel, shoot by instinct. End of day, relax tension and store uncocked. Used this way, the M5 becomes transparent — it records, you think. Nothing digital achieves that flow.

Maintenance — respecting the design

An M5 in competent hands is straightforward. The only unique element is the meter-arm geometry: it must retract precisely parallel to the film plane. Otherwise the arm grazes the gate or mis-reads. Any technician familiar with Wetzlar tolerances — DAG Camera, Sherry Krauter, Youxin Ye, or Leica Wetzlar Classic — can service it. Curtains, brakes, and gear lubrication follow the standard M4 procedure. CLA intervals of ten years keep them perfect.

Leica M5 with Voigtländer 50 mm f/1.1 — metered directly from the model’s cheek to hold mid-tone skin detail against the darker costume and woodland background. The M5’s spot meter made precise balancing effortless during this black-and-white session.

Buying guidance

Meter arm: smooth, free, no paint scrape inside gate.

Finder: bright patch, accurate vertical alignment.

Shutter: listen for even pitch from 1 s to 1/1000.

Battery well: clean threads, firm spring.

Lugs: two-lug early vs three-lug (post-1973). Three-lug hangs straighter with modern straps.

Inspect before purchase; avoid “dead meter” bodies unless priced for repair. The rest is routine.

Ownership economics

An M5 with a recent CLA costs less than a worn M6 and will outlast it. The mechanical systems are over-built, electronics minimal. Spares exist, and meter recalibration is a one-off. For working photographers who value independence from automation, it’s the most sustainable M — a camera likely to outlive its batteries’ patent cycle.

Collector and investment perspective

Market data show that M5 prices have risen steadily since 2015, with premium black-chrome bodies commanding 40–50 % more than silver. Jubilee editions, once undervalued, are now sought for their engraving and final-year provenance. Unlike speculative digital bodies, M5 values track condition and service history rather than nostalgia hype. Cameras with documented CLA by a recognised technician typically sell within weeks.

What’s notable is that the M5’s price floor is supported by working photographers, not just collectors. Its utility keeps demand stable even when broader Leica markets fluctuate. In that sense, owning an M5 is closer to holding a vintage lens: it’s both a usable asset and a mechanical archive of a company’s highest standard.

Top plate of the black chrome Leica M5 — the overhanging shutter dial sits forward for fingertip control while viewing, a design that defines the camera’s speed and precision. Beside it are the ASA/DIN film-speed selector and the X-sync port, all aligned along the M5’s heavier brass top plate that gives the camera its balanced feel in hand.

Cultural misreading and rehabilitation

For decades the M5 was shorthand for Leica’s “failure.” Journalists of the 1980s repeated clichés about size and looks. Then photographers began using them again, discovering a quieter, more practical camera. By the 2010s, M5s were rising in price while M6s plateaued. It is the most complete mechanical M ever made. The facts haven’t changed; perception finally caught up.

Commercial failure, mechanical success

The M5’s failure was timing, not design. It launched at the wrong economic moment — post-oil-crisis, rising yen, shrinking margins. Its cost approached that of a full Nikon F2 kit; its silhouette offended purists; and Leica’s own partnership with Minolta on the CL split attention. Dealers ordered fewer; production wound down by 1975. Yet every review that measured accuracy rather than aesthetics found excellence.

Comparisons to other M Cameras

M3 (1954–66): unmatched 0.91× finder and mechanical refinement; no meter, slower reload. In variable light the M5 is faster because you never leave the finder.

M4 (1967–71): ergonomically refined, still meter-less. The M5 is the logical evolution — metering integrated rather than attached.

M6 (1984–98): smaller silhouette, LED indicators, averaging cells, built in Solms under cost-controlled processes. Functional, less tactile.

M-A / MP (modern): pure mechanical excellence, but no spot meter and different production philosophy.

For metered, mechanical reliability, the M5 remains singular.

Summation — choosing by function

If you want maximum magnification and no meter: M3.

If you want classic ergonomics and no meter: M4.

If you want a meter with the vintage silhouette: M6.

If you want metering without surrendering mechanical purity: M5.

The choice reveals priorities. The M5 is the engineer’s Leica — a different decoration, with more intent.

Road-test conclusion & What “last true Leica” actually means

After twenty years with film and half a decade with the M5, I see no compromise in it. It is quieter than any SLR, steadier than lighter M cameras, faster in changing light than any meter-less body. It feels built for working photographers, not collectors. Those who dismiss it on looks are choosing styling over substance. For anyone serious about film as craft, the M5 remains the definitive metered Leica — the last made by hand, the last tuned by ear, and still the one that gets it right.

It is not nostalgia; it’s workflow. “True Leica” refers to mechanical lineage and bench standard. Each M5 chassis passed through the Wetzlar workshop one at a time. Subassemblies were matched by hand, tolerances felt rather than measured, and every final check signed by the technician. The next M, the M4-2, was built in Midland under cost-rationalised team assembly. The difference is tactile: a Wetzlar body feels damped, weight-balanced, and silent at half-press. That difference is why so many still time accurately fifty years on.

A literal road test, crossing Joshua Tree National Park — Leica M5 metered from the tarmac mid-tone to balance the deep sky and pale sand, holding both texture and density through the desert light. A perfect test of the M5’s spot-meter precision while shooting from a moving vehicle.

Key specifications

Production: 1971–1975, Wetzlar (Germany)

Quantity: 33 881 total (22 685 black chrome / 10 396 silver chrome / 1 750 Jubilee)

Viewfinder: 0.72×; framelines 35/50/90; in-finder speed display

Rangefinder base: 68.5 mm (mechanical); 49.3 mm effective

Meter: TTL spot; ~7.5 mm CdS cell; analog match-needle

Battery: PX625 1.35 V mercury; MR-9 + silver-oxide or Wein MRB625

Shutter: horizontal cloth; 1 s–1/1000 s + B

Dimensions / weight: 150 × 84 × 36 mm; 740 g (silver) / 775 g (black)

Notes: avoid collapsible lenses; verify deep-recessed wides; three-lug post-1973.

All images in this article were developed and scanned in-house and UK-wide lab at Liquid Light Lab, our dedicated 35 mm film development and studio based in Leamington Spa. Send in your film and you’ll get exceptional results, up to 60MP TIFF and JPEG scans, and rare pyrogallol for exceptional black and white images.

By Martin Brown | Liquid Light Whisperer