Zeiss Sonnar 50mm f/1.5 (1939) — The Lens That Drew Light Before Colour

The 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss Sonnar from 1939 is one of the great optical designs of the last century. It belongs to an age before coating, before marketing language replaced observation. It was built to interpret light, not to control it. Mine is one of the last pre-war uncoated examples, mounted on a Contax IIa body from the early 1950s — the bridge between the pre-war world and the modern one.

Uncoated light through colour — the 1939 Sonnar draws red as density and air, not saturation. The shadows fall gently, colour held in tension between film grain and glass.

Shot on decades expired Fuji Eterna film.

The Sonnar was never meant for colour, yet it handles colour with a gentleness that modern lenses have long forgotten. On Kodak Vision3 50D, it produces a natural softness — low contrast, deep tonal separation, and colour that feels more like atmosphere than pigment. Blues lean toward cyan, greens toward olive-gold, skin carries the weight of air and daylight rather than the sharpness of pixels. It draws like film remembers: continuous, subtle, cinematic. This kind of colour behaviour can only be seen on real film — developed in-house, not by an automated lab.

At full aperture, the Sonnar gives its signature look. Focus is precise but never sterile — the image breathes around the subject. Sharpness fades into blur as though light itself has softened at the edges. Modern optics often describe this as a flaw. It isn’t. It’s how the lens expresses distance, depth, and space. Light isn’t carved by this glass; it’s interpreted. When shooting portraits, that behaviour adds dimension to faces that digital sensors can’t reproduce.

Flare is inevitable with uncoated glass. I don’t hide from it. It’s part of how the Sonnar speaks. In backlight, the image glows with a soft veil that adds atmosphere and weight. The flare carries the colour of the sky into the subject. It unites the frame. I rarely use a hood unless absolutely necessary — the flare is part of the creative process, not something to be corrected.

On black and white film, especially on FPP “Mummy” film, the Sonnar returns to its natural language. The rendering is liquid and tonal. Shadow detail doesn’t collapse. Midtones roll cleanly, and highlights feel drawn rather than etched. There’s a tactile density to the grain that blends beautifully with the optical structure of the lens. Nothing looks forced. The combination of this pre-war design and a slow film gives a result that feels physical — an image you could almost touch.

These black and white shots were developed and scanned in the Liquid Light Lab, using the same Pyro and cinema chemistry available to clients.

Mechanically, the Sonnar feels unlike anything made today. The focus throw is long and deliberate, designed for bare fingers, not gloves. The aperture ring turns without clicks, allowing exposure to flow rather than jump. It rewards patience and precision — qualities that belong to the era it came from.

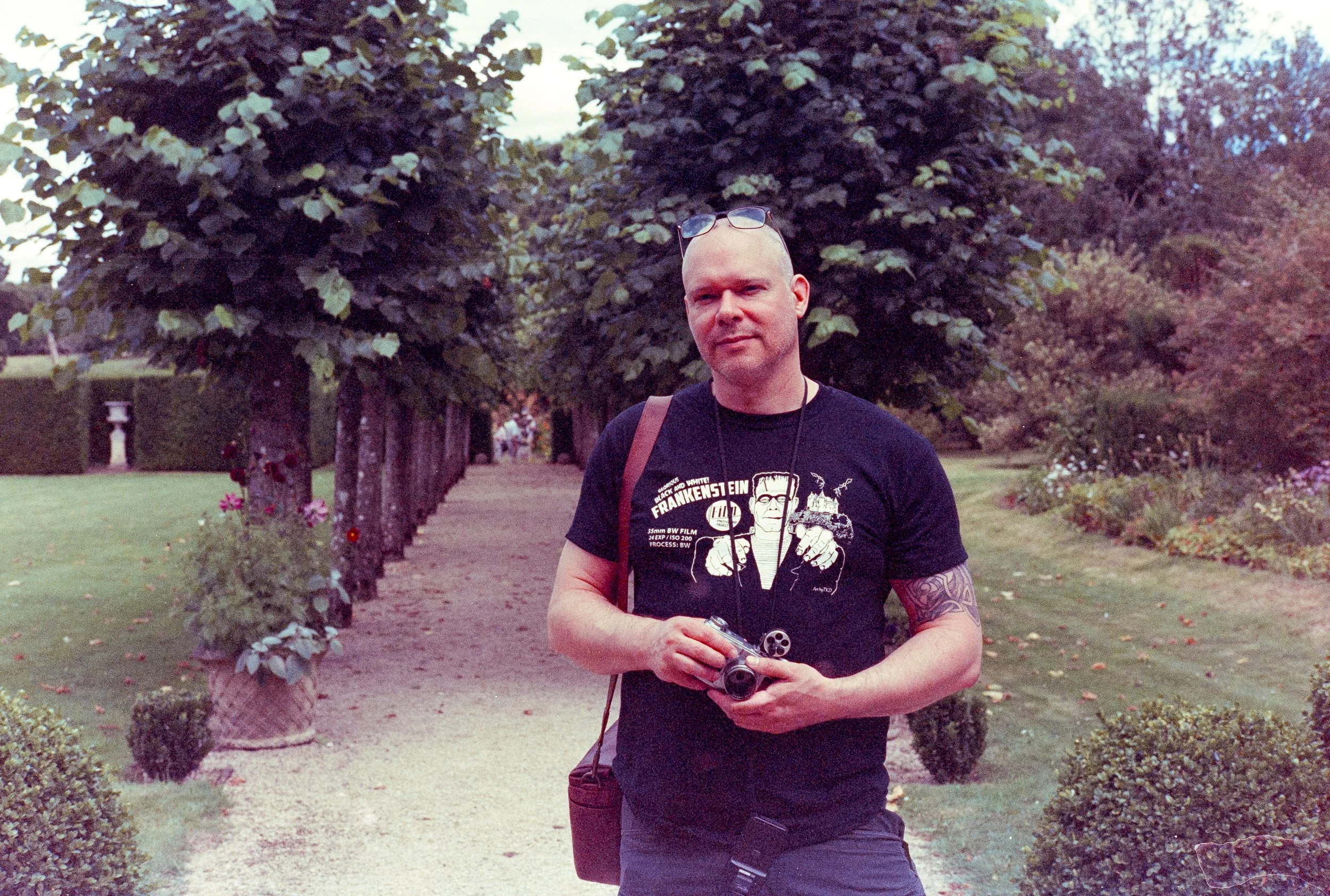

Me with the Contax IIa and the 1939 Zeiss Sonnar 50 mm f/1.5, shot on Fuji Eterna.

Only a few hundred of these lenses are likely still in use worldwide. Many have clouded or seized; others were destroyed or modified beyond recognition. Finding one that is clear, lubricated, and optically aligned is almost impossible. This one survived intact — clean, functional, and alive. It still renders light with the same quiet authority it had in 1939.

For portraits, the Sonnar is extraordinary. It is nothing like digital sharpness; it describes form and emotion. Every frame carries depth that exists beyond resolution. It transforms simple light into presence. The lens is not vintage for the sake of style — it’s cinematic craft. When used well, it speaks in the same tonal language as early cinema itself, when light was understood rather than captured.

If you ever find one of these lenses — even a dusty, frozen example — take the time to bring it back to life. It’s worth every hour and every penny to restore. There is no digital preset, no modern optic, no software filter that can replicate what this glass does naturally. Once cleaned and aligned, it becomes a direct line to photography’s origin — and a reminder that the most beautiful images often come from patience, imperfection, and craft.

For me, it isn’t nostalgia. It’s continuity — a living connection between the light of then and the light of now. For me, this lens has the same optical character I look for in these tests is what defines my cinematic portrait sessions — the same film, the same light, just in the scarcest possible form.

All images in this article were developed and scanned in-house and UK-wide lab at Liquid Light Lab, our dedicated 35 mm film development and studio based in Leamington Spa. Send in your film and you’ll get exceptional results, up to 60MP TIFF and JPEG scans, and rare pyrogallol for exceptional black and white images.

By Martin Brown | Liquid Light Whisperer