Push and Pull Film Processing: How Development Time Shapes Tonality, Density, and Cinematic Rendering

Film carries its own tonal language, and development is where that language is shaped with intention. In cinema and mid-century photographic practice, exposure and development were treated as two halves of the same craft: one creates the latent image; the other reveals it. Push and pull processing sits at the centre of this relationship. It allows photographers to refine contrast, density and tonal depth not through presets or correction after the fact, but through controlled chemical development that respects the physical structure of film. This article explains what push and pull truly are, why they matter for authored work, and how Liquid Light Lab executes these processes with the precision required for professional and cinematic photography.

Pulled two stops to ISO 100, this frame shows how Lomography 400 softens under reduced development. The highlights remain open, the colour stays clean, and the tonal transitions reflect the precision of Liquid Light Lab’s fresh-chemistry workflow.

What Push and Pull Processing Is

Push and pull processing allows a photographer to shape the tonal behaviour of film by adjusting development time. Extending or reducing development can compensate for exposure deviations or deliberately influence contrast, density and shadow structure. At Liquid Light Lab, these adjustments are executed using fresh chemistry for every roll, controlled timing, stable agitation and high-dynamic-range scanning. This approach produces consistent, predictable results suited to professional and cinematic work where tonal integrity matters, and clients want the best from their work.

Push and pull development is the controlled alteration of processing time relative to the exposure recorded on the film. Pushing extends development to build density in under-exposed negatives; pulling shortens development to restrain highlight build-up in over-exposed negatives. These changes influence how the film responds across the tonal scale and are part of the craft of working with analogue materials.

Misunderstandings in Push/Pull

Many photographers assume push and pull decisions only occur inside the camera, but metering differently is only the first half of the process. The exposure placed on the film creates the latent image, and then the lab determines whether that image becomes fully usable or collapses in the extremes. Rating Portra 400 at 1600, for example, under-exposes the film by two stops. The film does not become a 1600-speed stock; it simply receives less light. The tonal behaviour associated with pushing—deeper shadows, higher contrast, more pronounced grain—emerges in development, not at the moment of exposure. Pulling works the same way. Over-exposing the film provides additional highlight information, but only reduced development time preserves that latitude. Push and pull are therefore collaborative acts: the photographer controls exposure, and the lab controls interpretation.

Why Photographers Push or Pull Film

Photographers push film to maintain workable shutter speeds, define shadow tone or create a stronger, more dramatic contrast structure. They pull film to soften contrast, preserve highlight detail or create a smoother, more refined tonal progression, particularly in portraiture or controlled environments.

Because film carries its own tonal language, push and pull processing gives photographers deliberate, predictable ways of shaping it. This was as true in the controlled lighting of studio cinema as it is now in modern authored portraiture. Your lab is your partner, co-creating your vision.

Kodak Double-X pushed one stop, photographed on the Leica M5. The extended development lifts the midtones and tightens the contrast while the film’s highlight structure remains intact, shaped through Liquid Light Lab’s fresh-chemistry workflow.

How Pushed Film Behaves

When film is pushed, extended development increases density and contrast. Midtones separate more decisively, shadows deepen if latent detail exists, and grain becomes more visible as lower-exposure regions are amplified. C-41 emulsions such as Portra 400 show a marked contrast increase beyond +1 stop, and their colour palette becomes more assertive. Vision3 motion-picture stocks behave differently. Designed for cinema, they tolerate extended development smoothly, even at +2 stops, while retaining highlight shape and coherent colour. This behaviour is directly tied to their design lineage: Vision3 stocks were engineered to maintain consistency under dramatic exposure changes on set.

How Pulled Film Behaves

Pulled film behaves in the opposite way. Shortened development reduces contrast and limits highlight build-up. This creates a smoother tonal scale with controlled highlights and reduced density. Pulled negatives scan exceptionally well when handled with a high-dynamic-range workflow and are ideal for portrait work, bright landscapes or any situation where tonal separation matters more than contrast. When a photographer deliberately over-exposes HP5+ for a softer portrait or pulls Portra for extended highlight control, the effect is ultimately created in the controlled reduction of development time.

C-41 and ECN-2 Differences

C-41 and ECN-2 films respond differently to push and pull adjustments because of their intended use cases. C-41 films are built for predictable behaviour in still photography, producing controlled shifts when pushed or pulled. ECN-2 Vision3 stocks were engineered for cinema and offer greater latitude, smoother density changes and a more controlled response to large adjustments. Liquid Light Lab processes ECN-2 film using fresh Bellini chemistry rather than replenishment systems. This eliminates colour drift, accumulated by-products and developer fatigue, producing extremely stable and repeatable results.

Babylon 13 pulled one stop to ISO 6. Reducing development softens the contrast and preserves the highlights across the landscape, giving this road scene a long tonal scale shaped entirely in Liquid Light Lab’s fresh-chemistry workflow.

Push and Pull for Black & White Film

Black and white films respond even more directly to changes in development time. Their density is built entirely from metallic silver, with no dye layers involved. When pushed in 510 Pyro, contrast rises cleanly, midtones gain definition, highlights retain shape due to the stain mask, and grain remains surprisingly controlled. Even at +2 or +3 stops, pyro-developed negatives hold a coherent tonal structure. Pulled black and white film displays long, smooth tonal transitions and restrained highlights. In portraiture, this can produce an elegant, controlled rendering that remains consistent when scanned at 16-bit depth.

Use-Case Scenarios

Use-case scenarios illustrate the practical value of push and pull. A concert photographer shooting Vision3 500T at night may rate the film at 2000 to maintain shutter speed. The negative will be thin, but with extended development in fresh ECN-2 the shadows gain density, colour remains stable and the high-contrast environment becomes readable without digital clipping. A portrait photographer may shoot Portra 400 at 200 to achieve a luminous over-exposure. Reduced development time then preserves highlight texture and produces a smooth tonal gradient ideal for skin. A black & white landscape photographed on HP5+ at EI 160 may use a –1 pull to extend highlight detail in a bright, reflective scene. In each case, the final aesthetic is created through controlled chemistry, not simply through exposure.

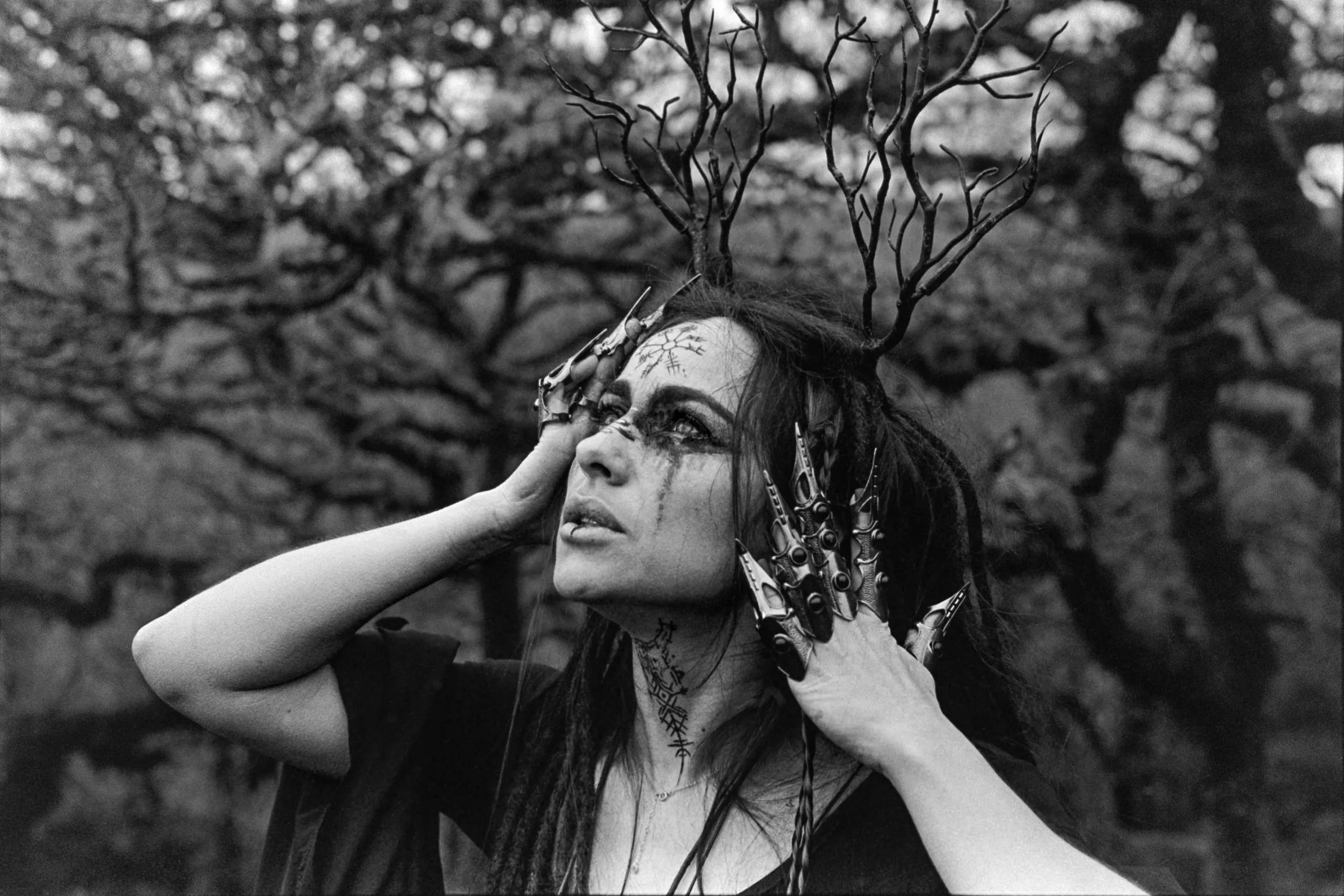

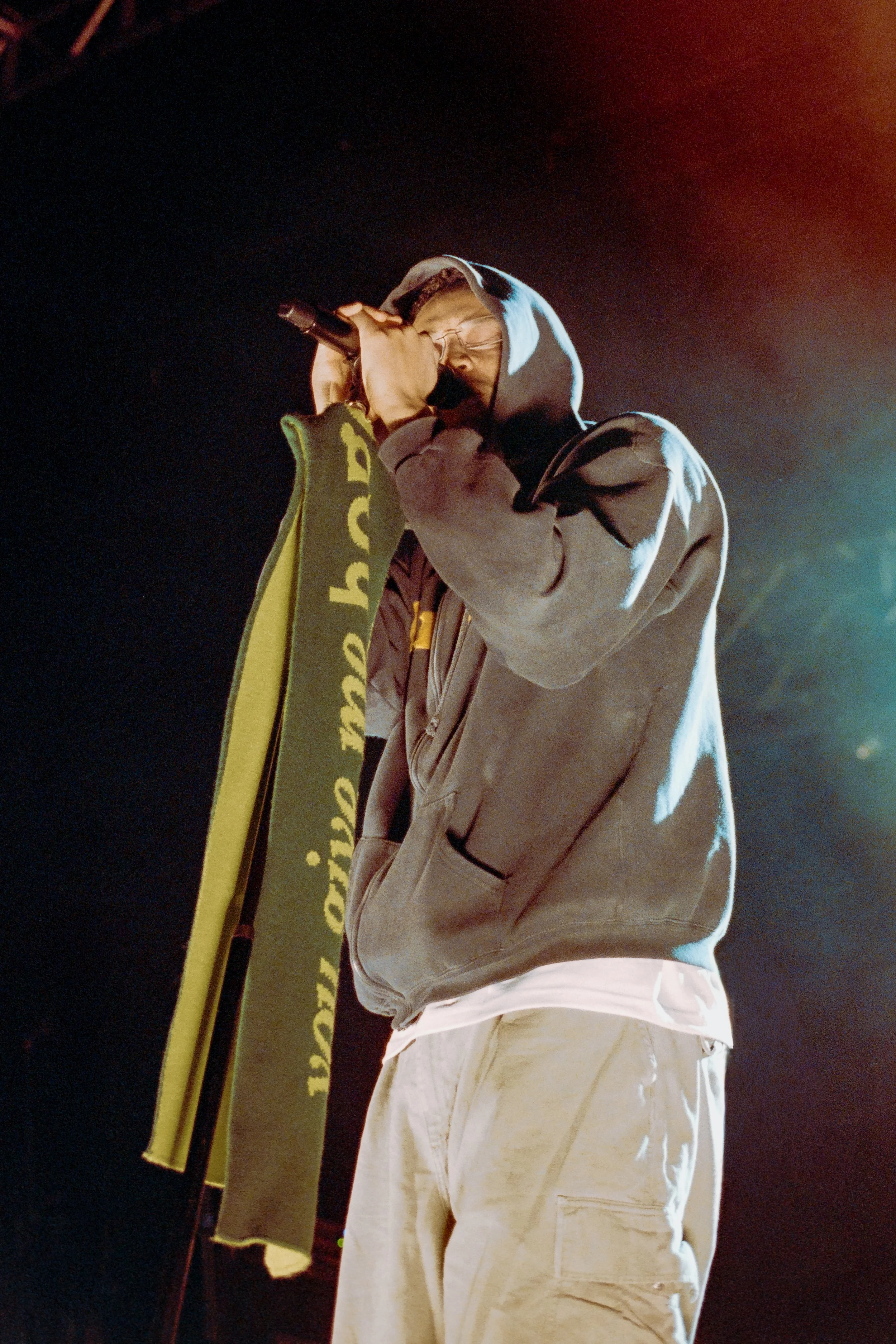

Kodak Portra 400 pushed two stops to ISO 1600. Extended development builds density in the shadows while keeping the colour stable under stage lighting, shaped through Liquid Light Lab’s fresh-chemistry workflow. Image kindly supplied by Liquid Light Lab customer Jay West, @jxywst.

How Liquid Light Lab Executes Push and Pull Processing

At Liquid Light Lab, push and pull processing is governed by a simple principle: every roll is given fresh developer, whether it is colour, motion-picture or black and white. This eliminates the variability associated with reused or replenished chemistry. Fresh chemistry behaves predictably, producing identical contrast behaviour and colour stability across all rolls. Times are set per stock and per requested stop, using density behaviour as the reference rather than generic charts. Agitation cycles are kept stable because agitation directly influences local contrast and uniformity. Temperature is held to tight tolerances because even slight variation affects pushed film significantly. Once development is complete, every negative is scanned at 16-bit depth, up to 60 megapixels, and 13–14 stops of dynamic-range. This ensures that pushed film retains shadow structure and that pulled film holds its highlight nuance without flattening.

What This Means for Photographers

What this means for photographers is straightforward. Exposure choices in the field are only the foundation of your image. The laboratory—not the camera—determines how that exposure is interpreted. Their chemical selection matters, and not all C-41, ECN-2 or black and white developers are equal. Some truly are pinnacles of chemistry, and only to be found in boutique labs like the Liquid Light Lab; you will see the difference.

Push and pull processing is not about rescuing mistakes but about shaping the tonal language of the film in a repeatable, intentional way. This is part of why film retains its distinct place in cinematic and authored photography: density manipulation is part of the creative process, and not a corrective step.

Typical Push and Pull Amounts

Different levels of push and pull create distinct tonal effects. A +1 push is moderate and controlled, suitable for most films. +2 creates a more dramatic contrast profile, and Vision3 films handle this particularly well. +3 is specialist territory and requires intentional exposure choices. A –1 pull is excellent for portraiture, producing controlled highlights and gentle tonal transitions. –2 is a strong compression ideal for soft, refined rendering when the look requires it.

Persistent Misconceptions

Several misconceptions persist globally about push and pull processing. Pushing does not change a film’s true ISO rating; it changes how the lab develops the film. Metering alone does not constitute a push—development must match the exposure adjustment. Pulling does not simply make film “brighter”; it reduces contrast by restraining development. Over-exposure is not a pull until the lab shortens development time. And most importantly, the camera and the lab each perform half the work; one does not replace the other.

Why Fresh Chemistry Matters

Fresh chemistry is central to why Liquid Light Lab’s results are consistent. Many labs rely on replenished systems where developer activity shifts gradually. This affects contrast, colour balance and density. By using fresh chemistry for every roll, the Lab removes these variables, ensuring consistent tonal behaviour and stable colour across all sessions. This makes push and pull development a predictable, reliable tool rather than an uncertain adjustment.

Kodak Aerocolor 100 pulled one stop to ISO 50. Reducing development softens the contrast and opens the highlights, giving the frame a smoother tonal register shaped through Liquid Light Lab’s fresh-chemistry workflow.

Cinematic Relevance

From a cinematic perspective, push and pull adjustments shape how the negative holds shadow detail, rolls off highlights and manages contrast transitions. This is fundamental to the visual language of film. A pushed Vision3 negative retains the compressed shadows and high contrast associated with night exteriors, while a pulled Portra negative mirrors the tonal smoothness of 1960s studio portraiture. These are not surface-level “looks” but structural changes in density that give film its recognisable presence.

What Clients Receive

Clients receive negatives with consistent density, repeatable colour rendering and accurate tonal structure whether the film has been pushed, pulled or processed normally. Shadow detail is preserved on pushed rolls, highlight detail is maintained on pulled rolls, and the full tonal range is retained through high-dynamic-range scanning. Both TIFF and JPEG files are provided as standard, suitable for professional printing or archival use.

Kodak Portra 400 pushed two stops to ISO 1600. The extended development maintains colour stability under rapid stage lighting shifts and preserves usable shadow density in a high-contrast concert environment. Image kindly supplied by Liquid Light Lab customer Jay West, @jxywst.

Service Availability

Push and pull services are available for C-41 colour negative, ECN-2 motion-picture stock and black and white film, and can be ordered directly through the Liquid Light Lab page. For the adventurous, we even have a dedicated C-41 cross processed in ECN-2 service page suitable for remjet removed films like Cinestill, Candido and others.

Conclusion

Liquid Light Lab operates as a dedicated film-processing facility specialising in C-41, ECN-2 and 510 Pyro development with high-dynamic-range scanning. All processes are executed in-house with density-targeted control and consistent colour management. The Lab is built around craft, discipline and technical competence—qualities that allow push and pull processing to function as a reliable creative tool rather than a variable.

By Martin Brown | Liquid Light Whisperer

All images in this article developed in the Liquid Light Lab.