The Secret Behind Film’s Tonal Depth: How Pyro Developers Shaped Black and White Photography

Pyro developers have shaped black and white photography since the nineteenth century. Long before fine-grain modern chemistry and digital scanning, photographers sought ways to extend tone, preserve highlight texture, and control density with precision. Pyrogallol became their answer — a developer that tanned the emulsion, stained the negative, and revealed light with a depth no other formula could match.

Origins — The Birth of Pyrogallol Development

Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, Ansel Adams (1927). From the original negative now in the public domain in the U.S.

The first recorded Pyrogallol formulas appeared in the 1880s, introduced to replace iron-based developers that were unstable and prone to fog. Pyro’s unique property was its staining effect — as it reduced silver, it simultaneously hardened and coloured the gelatin. This gave early negatives a dual image of silver and dye, increasing contrast on soft-toned printing papers and improving highlight separation.

By the turn of the century, Pyro had become the professional standard. Its ability to preserve texture and tone made it the preferred choice for glass plates, large-format sheet film, and the meticulous exposures of early landscape photographers.

The Golden Era — Adams, Weston, and the Zone System

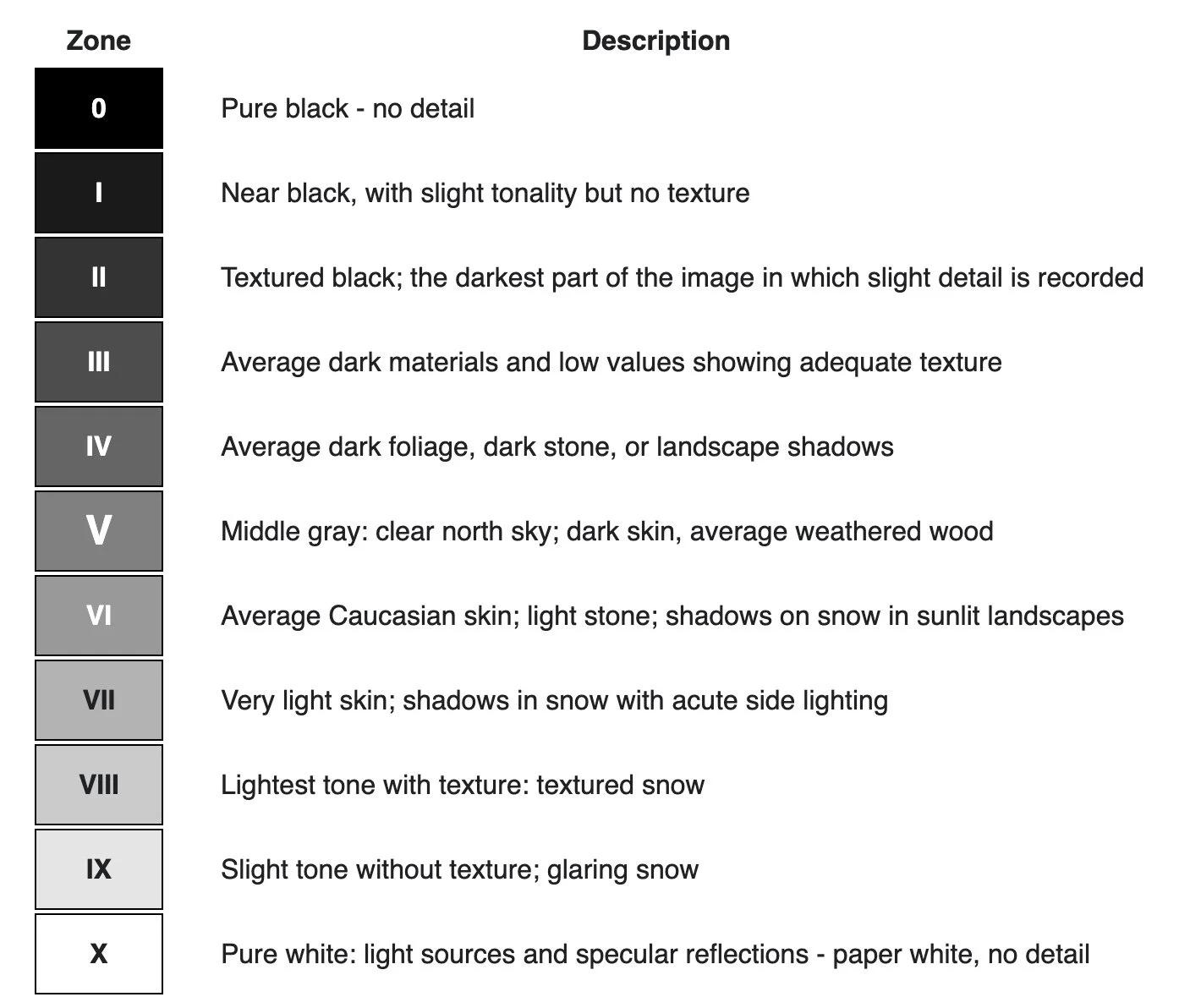

The Zone System, formalised by Ansel Adams and Fred Archer, mapping tones from pure black to pure white with defined texture and subject references. Courtesy of Wikipedia (1981).

In the early to mid-twentieth century, Pyro found its most famous advocates. Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and other Zone System pioneers relied on Pyro for its long tonal curve and ability to handle extreme contrast scenes. Adams’ negatives from Yosemite, printed decades later, still exhibit the smooth highlight roll-off typical of Pyrogallol development. Pyro allowed these photographers to “place” tones with mathematical precision — the foundation of the Zone System itself.

While some later shifted to developers like D-76 for convenience, the tonal language of fine-art black and white owes much of its vocabulary to Pyro’s density control and subtle separation of tone.

Transition — Decline and Rediscovery

By the 1970s, Pyro had largely vanished from commercial labs. Concerns about toxicity and the rise of general-purpose developers made it a specialist’s tool. Yet among darkroom purists, its reputation endured. Photographers who compared Pyro negatives to those from newer formulas found that nothing else offered the same highlight smoothness or archival hardness.

The 1990s brought a quiet resurgence. New formulations such as PMK Pyro (by Gordon Hutchings) reintroduced the chemistry to modern emulsions with improved safety and consistency. This renewed interest set the stage for a new generation of Pyro developers designed for both darkroom printing and digital scanning.

Modern Precision — The Arrival of 510 Pyro

Edward Weston in his early years with a large format camera. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

510 Pyro, created by photographic chemist Jay DeFehr and produced by Zone Imaging in the UK, represents the most refined stage in more than a century of Pyro evolution. The formula is built around Pyrogallol, ascorbic acid and triethanolamine — a combination that delivers remarkable sharpness, clean shadows and stable stain density with low toxicity and excellent keeping properties.

Where early Pyro demanded meticulous darkroom control, 510 Pyro provides consistency without compromise. It’s a single-solution concentrate that stores well, mixes cleanly and behaves predictably in rotary processors or hand-inversion tanks. The developer’s proportional stain acts like a built-in tonal map, giving negatives that scan with a balance of density and transparency that most other formulas cannot achieve.

In high-resolution digital scanning, 510 Pyro is particularly powerful. The stain moderates density in the highlights, allowing the sensor to record subtle gradations that would otherwise compress. Grain structure is softened but never blurred, giving a clarity that feels optical rather than digital — the negative breathes, and light rolls through it instead of stopping abruptly.

The chemistry’s tanning action also hardens the emulsion, improving resistance to scratches, swelling and long-term degradation. Properly fixed and washed, a 510 Pyro negative will remain stable for generations, its image silver protected by the very stain that defines its tone.

At Liquid Light Lab, every Pyro roll is developed exclusively in Zone Imaging 510 Pyro — chemistry that unites the legacy of Adams and Weston with the precision required for cinematic scanning and modern archival standards. It’s the bridge between the darkroom and the digital world: authentic, repeatable, and built to last.

Develop your film in 510 Pyro →

Why Pyro Endures

Pyro’s survival across 140 years of photographic chemistry says everything about its quality. It doesn’t merely develop a negative; it shapes how light is interpreted. The balance between metallic silver and proportional stain creates an image that feels continuous — less an array of tones than a gradient of light itself.

For photographers seeking permanence, tone, and control, Pyro remains the benchmark. And in 510 Pyro, its lineage continues — leaner, safer, and more exacting than ever.

Just for once, all images in this article were not developed and scanned in-house and UK-wide lab at Liquid Light Lab, our dedicated 35 mm film development and studio based in Leamington Spa. We weren’t born at the time to develop them, but despite that, send in your film and you’ll get exceptional results, up to 60MP TIFF and JPEG scans, and rare pyrogallol for exceptional black and white images.

By Martin Brown | Liquid Light Whisperer